Unspooled

This June in the Main Gallery we are featuring Core Artists Joel Moskowitz and Sylvia Vander Sluis. Their exhibition, Unspooled will run from June 5 through June 30 with an opening reception on Friday June 7 from 6-8 PM. Below the artists discuss their ideas and process.

Sylvia Vander Sluis

On Weaving:

My previous collage painting came to a natural end a couple of years ago. In seeking a new direction, I reflected on the themes of my practice over the past few decades. I’ve consistently enjoyed synthesizing different materials and techniques – in other words, weaving metaphorically. “What about trying actual weaving?” I wondered. Having created handmade-paper and fabric art earlier, I already knew I’d enjoy working with fiber. I discovered SAORI, a Japanese improvisational weaving technique, which gave me lots of design freedom.

Evolution of Torso Series:

I began draping and pinning my woven material on the studio wall, quickly seeing sculptural opportunities. Wanting to bring the forms off the wall, I began experimenting with armatures, using weaving as the outer skin. The torso shape suggested itself early on – it is both a figurative reference, as well as a platform for my fibers and fabric. I remember how wonderful it was to walk around my first three-dimensional torso hanging in my studio, literally hugging it and enjoying its physicality. In time, I began to identify with the torsos as symbols of my personal energy, my energetic center. I imagined using the torso as a foundation for expressing different emotional states with fiber and fabric.

Personal History in My Art:

I have some significant challenges in my personal life. To keep my reservoir of energy, hope, and creativity full, I need to take care of myself. I want to do more than just cope; I want to flourish as a person and an artist. The themes of my current work spring from this desire to stay strong in my life – emotionally, mentally, and physically. My knitted and woven figures embody both my resilience and vulnerability, giving my personal feelings a physical presence that has emotional power. I like the idea of making what is most vulnerable in us strong and beautiful.

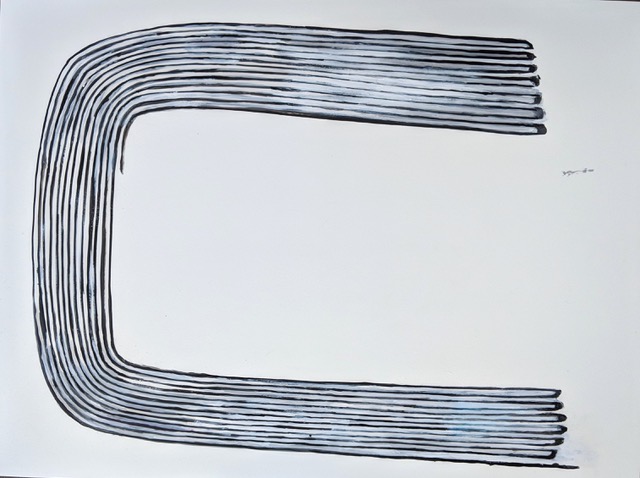

Joel Moskowitz

The Evolution of "Three Graces"

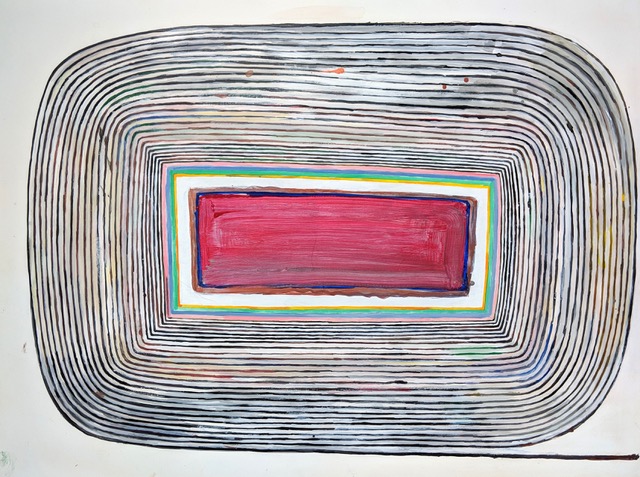

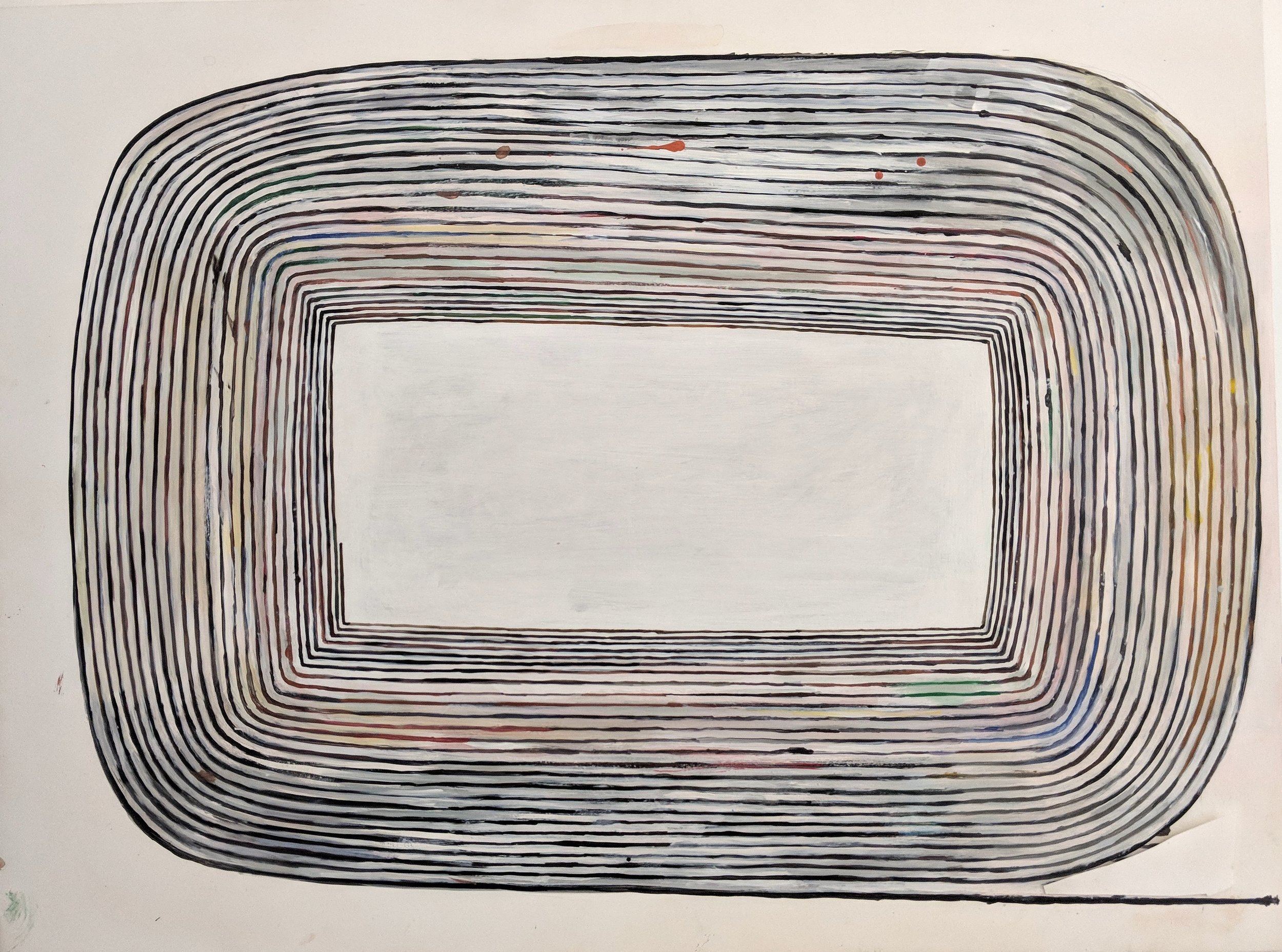

I started my new series by making spirals. But is it enough to just make spirals? They're universal symbols, but shouldn't I say something personal? Political? Unique for our time? So I painted colorful and metallic shapes in their centers. The colors seemed to represent planets, so I was still thinking universally, not personally, and I felt dissatisfied.

This painting that became "Three Graces": I tried a pinkish-red center. Then a whitish center. I liked both versions, but admitted to myself that I didn't know what they meant.

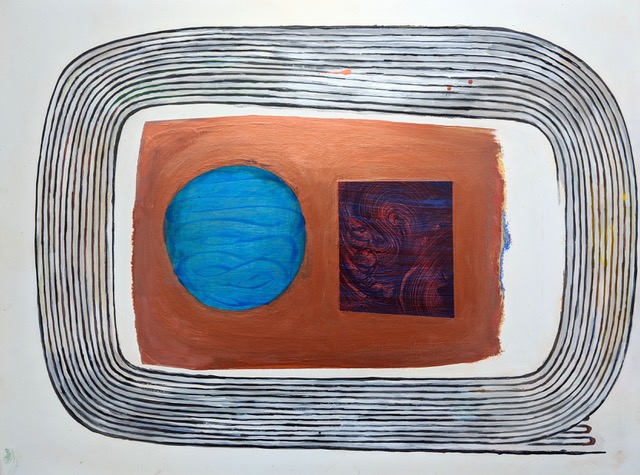

I tried a coppery field in the center, placed some plastic bottle caps on top, influenced by other artists I admire who use recycled materials. But, with a show coming up, I wanted to maintain a more or less unified body of work, and I realized the bottle caps, their three-dimensionality, their bright colors, were going in a distant direction.

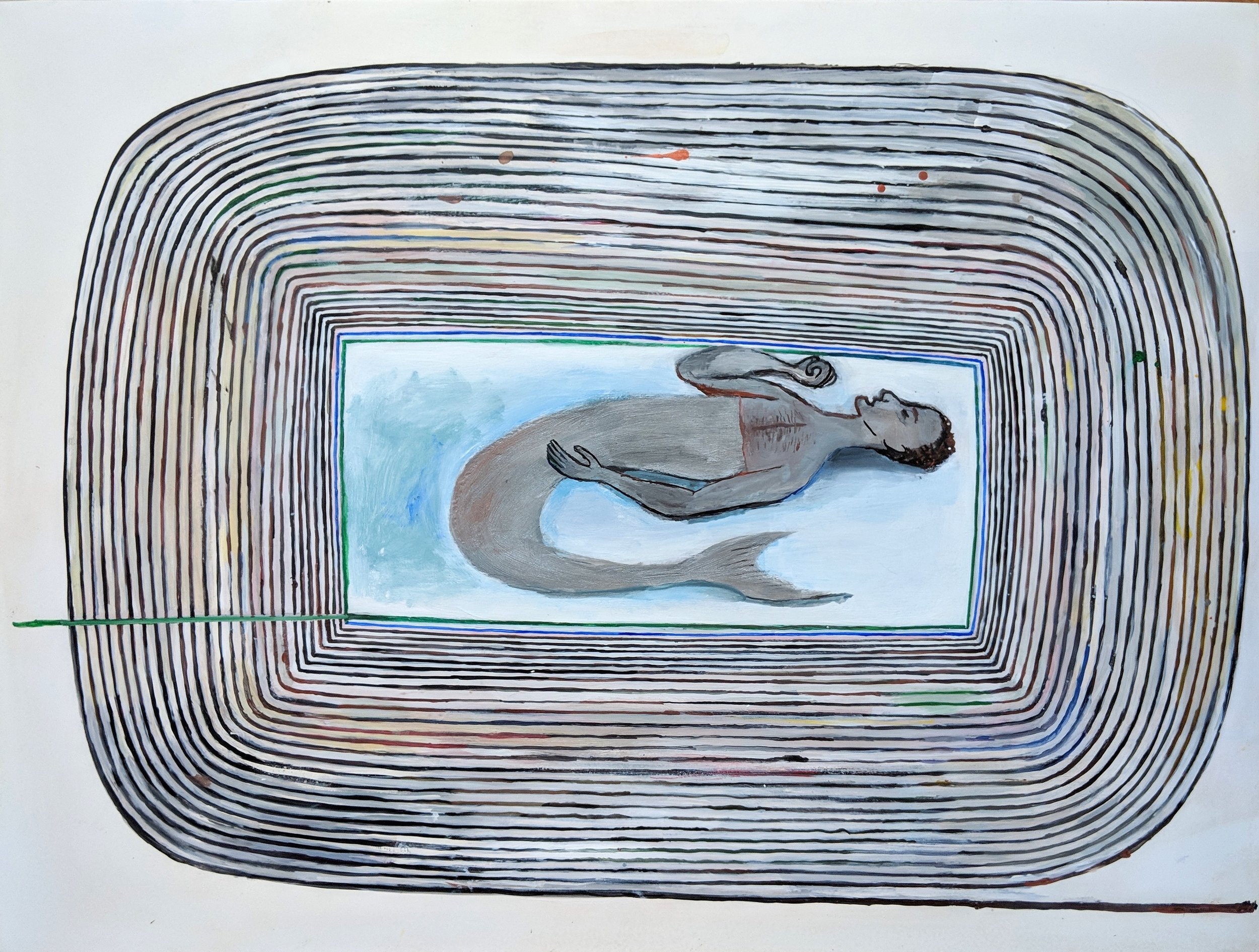

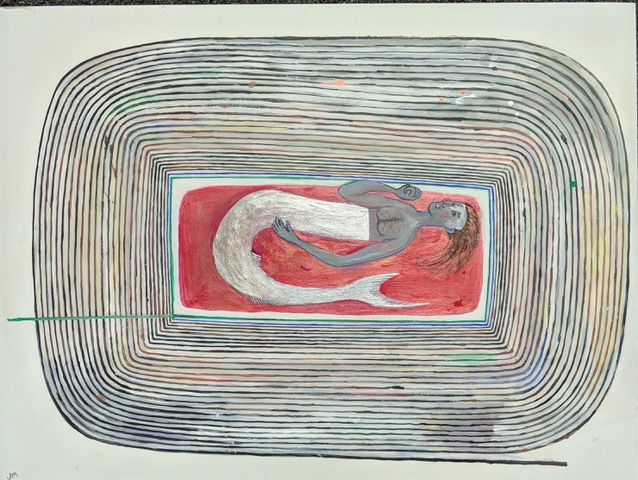

I painted a mer-man. He was trapped in a labyrinth, knocking to get out, and personified my claustrophobic tendencies. Then the blue sea became a pool of deep magenta; and the mer-man became a mermaid. She represented my feminine side.

My show with Sylvia Vander Sluis, "Unspooled," was approaching. I realized this piece was perhaps one of my best, but it was anomalous in my series of work, and would be a distraction. I decided to sacrifice it.

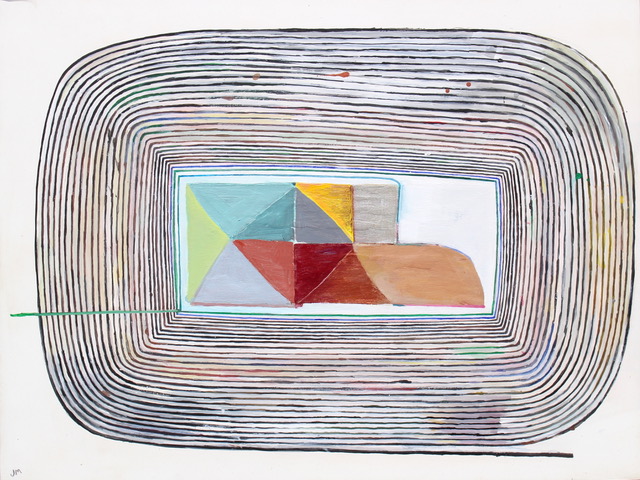

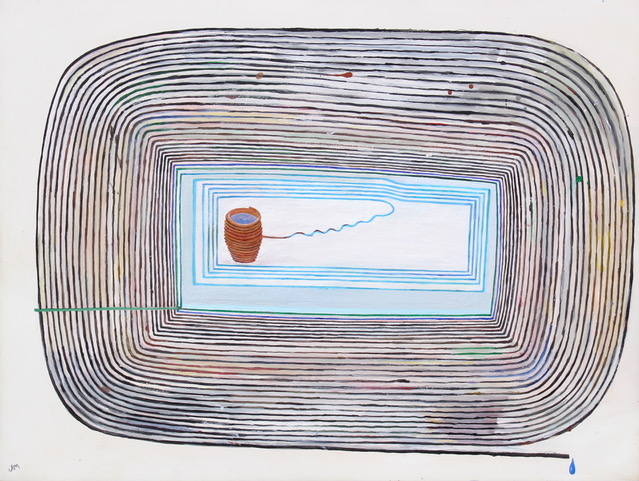

While I worked more efficiently on other paintings, this one was giving me grief. I tried abstract shapes in its center, in colors of the American Southwest. Then, I painted an object to mimic the spiral. It was a coiled vessel for holding water, and it spoke to me of irrigation, a vital topic, but not my topic.

Finally I collaged three illustrations of butterflies that I had cut out of a vintage dictionary given to me by a friend. Now I felt that the painting was similar to other recent works of mine incorporating animals, and would show well alongside them.

When I look back at the history of the painting, part of me feels sad for all the rejected images that lie underneath. Each one had some integrity and was almost complete. I painted over their colors, rubbed out their faces with sandpaper, scraped off their textures with a razor blade.

In the end, I decided to remove one of the butterflies, a Monarch. My wife had planted a grove of milkweed, but only one Monarch showed up to feed on the leaves and make its chrysalis. We hoped it would survive.

My purposeful erasing of the Monarch on my painting represents my process of creating by destroying images; while at the same time the resulting emptiness introduces the theme of life's fragility. The emptiness is the painting's focal point: a blue rectangle, like the sky, from which a Monarch butterfly has disappeared.